Too much, too young: 'Half of all Syrian refugee children are working'

Naseem, his wife, Maha, and their seven children live in a small, dark apartment in the north of Jordan. It’s November when we meet the family and already the chill of the approaching winter can be felt throughout the apartment.

The family from Daraa, Syria, tell us they escaped to Jordan in May 2013, and first settled in Za’atari Refugee Camp. Maha described her children’s fear during the conflict, “they used to hide under my dress whenever there were shootings and bombings.” Naseem tells us he sustained a gunshot wound to the leg, “I had to crawl on my back to move. It was so hard that I asked my wife to take the children and leave without me” he recalls. To this day, Naseem still struggles with his injury and is hardly able to move.

Winter is a big challenge for refugees living in basic accommodation. “In winter, it gets really cold in Jerash. We were living in another small house up the hill, but we had to move to our current house because I have painful surges in my leg when it is cold and it is extremely painful,” explains Naseem.

Besides the approaching winter, there are other challenges for Naseem and Maha’s children. Their youngest child, five-year-old Amir, seems distant and detached as he talks of regular beatings by his neighbour’s son.

Amir’s older brothers, Yaman and Mohammed, face different challenges. They have responsibilities that go far beyond their ages. Because of their father’s injury, they are the breadwinners for the family.

Amir’s older brothers, Yaman and Mohammed, face different challenges. They have responsibilities that go far beyond their ages. Because of their father’s injury, they are the breadwinners for the family.

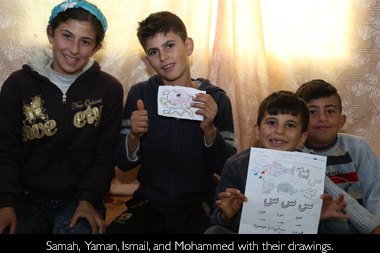

Eight-year-old Mohammed sells gum on the streets, earning 2to3 Jordanian Dinar (JODs), which is about £2.15, per day.

Ten-year-old Yaman works 12 hours a day in a coffee shop earning another 3 JODs. “I know how to make Turkish coffee and tea. I don't have a single day off to rest and I cannot see my friends,” says Yaman, with an expression of concern. “I want to become a police officer when I grow up to help people protect their rights, but I do not know how to read or write like everyone else.”

Sahar Yassin, World Vision’s Advocacy Advisor, explains some of the issues children encounter; “In Syria, the main threats to children’s physical safety are violence, kidnapping and torture. In Jordan, the crisis, now in its fifth year, has heightened different protection concerns for Syrian children. The combined effects of displacement and economic destitution have put Syrian refugee children at higher risk of violence and exploitation, including child labour, gender-based violence and early marriage.

“Approximately half of all Syrian refugee children are the joint or sole breadwinners for their families in Jordan. These children often do work that jeopardises their physical, mental and moral well-being, preventing them from acquiring the education they need and infringing on their basic human rights. Nearly 100,000 Syrian refugee children are missing out on a formal education, leaving them with sub-standard education or no education at all, posing a risk to an entire generation. The international community must remember that these children are the future of Syria and commit to more robust actions to protect the future of thousands of Syrian refugee children.”

Seven-year-old Ismail and 12-year-old Samah are the only children in the family continuing their education. Ismail is excited when he tells us about school and the numbers he has learned. Even though he is not a registered student due to a lack of spaces, the teacher allows Ismail to sit in the back of the classroom to listen and learn how to read and write. Although he doesn’t have friends at the school and he is not a registered student, Ismail says he enjoys attending classes, reading the Quran and learning new things.

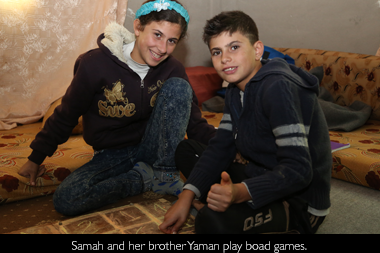

His sister, Samah, keeps a smile on her face and tells us her favourite subjects at school are Arabic and English. She is the only child to formally and officially attend school. At her age, however, Samah should be in the seventh grade, but her education was interrupted for three years and so she’s still in fifth grade.

His sister, Samah, keeps a smile on her face and tells us her favourite subjects at school are Arabic and English. She is the only child to formally and officially attend school. At her age, however, Samah should be in the seventh grade, but her education was interrupted for three years and so she’s still in fifth grade.

Samah attends World Vision Jordan’s remedial education classes, which are part of the No Lost Generation (NLG) project.

Naseem wishes all of his children could receive an education but understands the strain that the conflict in Syria has put on neighbouring countries, including Jordan. He tells us he is massively grateful for the country’s generosity and that they have opened their schools to Syrian children.

The family’s only source of income, in addition to what Mohammed and Yaman are able to earn, are the World Food Programme vouchers for extremely vulnerable families. The vouchers provide 15 JODs (around £14.85) per person, per month, just over half of what they used to provide. Although the family is surviving, their nutritional needs are not being met. “We are only eating two meals per day,” says Naseem.

As winter approaches, Naseem and Maha are concerned. Their children do not have winter clothes, nor does the family have warm blankets or a heater. “If we are warm, we will not have to eat to keep our bodies warm,” said Naseem.

Maha tells us she is willing her family to survive until they are able to return to Syria.

As winter descends, World Vision has been distributing essential winter kits to families to ensure they are not going cold this year. The kits contain blankets, plastic sheets, rope, a heater, carpet and mattresses.

To find out more and help, please visit our Refugee Crisis Appeal here »