The Hidden Legacy of Sexual Violence in Conflict

World Vision UK Senior Policy Advisor, Erica Hall, recently visited Northern Uganda to see the work World Vision is doing to help those affected by violence in conflict.

Barely a week goes by that we do not hear new reports of sexual violence in war zones – in South Sudan, Syria, Nigeria, Myanmar, Iraq and elsewhere. Sometimes these include the stories of survivors who have fought for justice, who are suffering stigma in their communities for the crime committed against them, who are struggling to rebuild their lives. I hear first hand countless heart-breaking stories of the consequences of acts of sexual violence committed during armed conflict – by both soldiers and civilians. And yet each time I am shocked, sad and angry all over again. I hope these feelings don’t go away – that I never become immune to the horror of them.

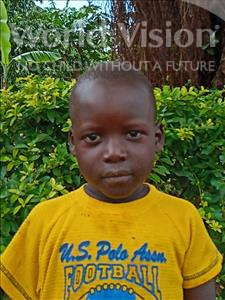

Some stories break my heart like no others. The histories of children born of rape in war are less known, but no less traumatic. Often rejected by their families and communities, they can face extraordinary struggles trying to find the place in the world, while coming to terms with their own DNA.

In northern Uganda, thousands of children have been born in captivity – the products of a ‘forced wife system’ used by Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) for systematic sexual violence and to create the next generation of LRA fighter. During the 1990s and 2000s, the LRA abducted and estimated 30,000 children, many as young as 8 or 10 years old. Of these, as many as 10,000 were girls, who were forced to become fighters and wives of commanders. Repeatedly raped, many gave birth while still children themselves. The number of children born in captivity is unknown, many hidden because of the stigma their mothers feel. At least 2,000 have been documented so far, and thousands more are likely to exist.

Over the past five years, I have met scores of these children, hearing their stories and finding out World Vision and the international community need to do to improve their situation. I met James who, having watched his mother be killed in front of him, escaped with his younger brother and ‘returned’ to a community he had never known. On the face of it, James was one of the lucky ones. His grandmother took both boys in and World Vision supported them, building a house for them to live in and helping to get James and his brother into school. But a year after returning, James was shot in the head by a man who thought he was a danger and didn’t want him in the community. He was only 15.

Late last year I met Sylvia, who came ‘home’ with her mother when she was 10. She was sent to live with an uncle when her stepfather didn’t want her in the house. Her uncle sexually abused her and she became pregnant. When I met her, she was in foster care, with her 6 month old baby. She is only 13.

So what can we do to help these children and the thousands of others born in captivity? One young man I met, 19 year old Michael very directly told me and a group of his peers that the solution is to hide their identities, get an education and leave their families and communities behind. In a culture based on clan and identity, this is a lonely thought that continues to haunt me.

But this where World Vision comes in.

In a project is funded by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, we’re working with faith and community leaders to end stigmatisation of former child soldiers and their children. To change the narrative on whom they are and how they should be treated. We’re also developing youth activists and helping change attitudes among young people.

We’ve seen a dramatic change. In Gulu, northern Uganda, communities are coming together thanks to this transformational work. During my time in Gulu in April, I marched through the streets of Gulu with colleagues, children and leaders many faiths behind the banner ‘Accept Me as Your Child’. Hundreds greeted us along the way and joined us for a day of testimony, prayer, singing and dancing to celebrate children born in captivity. This is a baby step in a long journey to bring these children out from the darkness, to creating a world where they do not need to remain hidden in order to succeed.

While I was there, I caught up with Michael, who I first met in 2014 barely three months after he had escaped from the LRA. At the time, he was just learning how to hold a pencil and was desperately trying to find a place to belong. Yet he drew me a very detailed picture of what life was like in the bush and his journey to freedom. Now, he lives with his aunt and uncle. He goes to a boarding school, where he is near top of his class. Nearly 20cm taller and with a huge grin on his face, he was barely recognisable from the boy I met less than 3 years ago. He is building a whole new life, thanks to the help of World Vision and its partner organisation, Watye Ki Gen (the aptly named community organisation women who had been abducted by the LRA, meaning ‘We have hope’ in Acholi).

Children like Michael are beginning to flourish, but still face obstacles. And there are many more who remain cast out by their communities and families, feeling lost and alone. They’ve suffered far too much. Today, as we celebrate the United Nations’ International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict, we owe it to them to step up and help. They have tremendous gifts to offer and deserve to be listened to and heard. It is up to all of us to make sure they no longer need to hide in darkness.

Find out how you can support our work in Uganda.